Recent Posts

RBA Is Actively Blowing Up Australia's Biggest Debt Bubble Until It Breaks

Posted by on

Australians must quickly come to the realisation that the country is suffering from a chronic failure of public policy as it relates to official interest rates and the Australian Government’s monetary policy framework.

Last week, the board of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) kept official interest rates at 1.5 per cent, the 24 th consecutive month since August 2016.

Moreover, the Governor of the RBA, Dr Philip Lowe, has stated that that he doesn’t expect Australia’s official rate of inflation to reach 2.5 per cent until 2021, meaning that official interest rates are at least on hold for the foreseeable future given the RBA’s official inflation target of an average of 2 per cent - 3 per cent over the economic cycle.

However, there can be little debate that Australia’s current regime of ultralow official interest rates has been one of the prime catalysts for the development of the largest structural imbalances within the Australian economic history, in particular as it relates to record household and foreign debt and declining rates of household and national savings.

The fact that the RBA’s monetary policy framework, in conjunction with other complementary economic policies such as generous taxation and welfare incentives, has allowed such structural imbalances to materialise is a clear indication that the framework that underpins the conduct of Australia’s monetary policy (including the role of the RBA) has broken down.

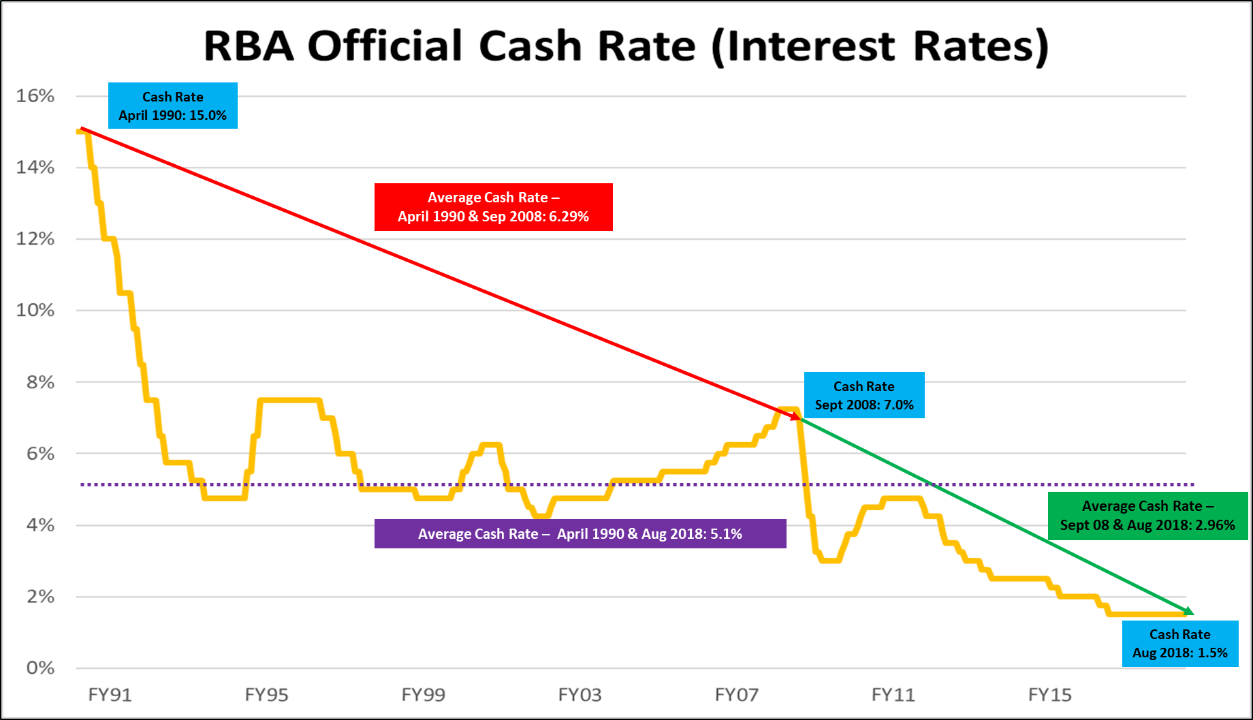

Since the last recession in 1990/91, when official interest rates reached a high of 15 per cent in April 1990, the RBA, through the implementation of its monetary policy framework, has engineered official interest rates, over the course of 28 years, to their lowest ever levels in Australia history.

The implications of such ultralow interest rates are both profound and disturbing.

As noted in a column I published last year with the Spectator Australia titled, Australia: Trapped by Cheap Credit [1], Australia’s economic policy makers have allowed Australia to be caught in a household debt bubble so large that the RBA has no capacity to normalise official interest rates back to their long-term average over this economic cycle which currently stands at 5.1 per cent (i.e. from April 1990 to August 2018), without causing significant economic damage to the household sector and the broader Australian economy.

Such policy incapacity represents a chronic failure of public policy.

Nevertheless, as early as 2012, working as an economic and political advisor in Federal Parliament to Senator Arthur Sinodinos, I have continued to advise parliamentarians both publicly and privately that a concerted effort is required by the RBA to raise interest rates in order to pre-emptively stem the growth of the household debt bubble, if not burst the bubble, irrespective of the Government’s official rate of inflation.

This action, even if it led to a mild economic recession, would be superior to allowing the Australian economy to experience a catastrophic economic crisis resulting from an uncontrollable international economic shock as was the case in previous Australian economic depressions, namely in 1892 and 1931.

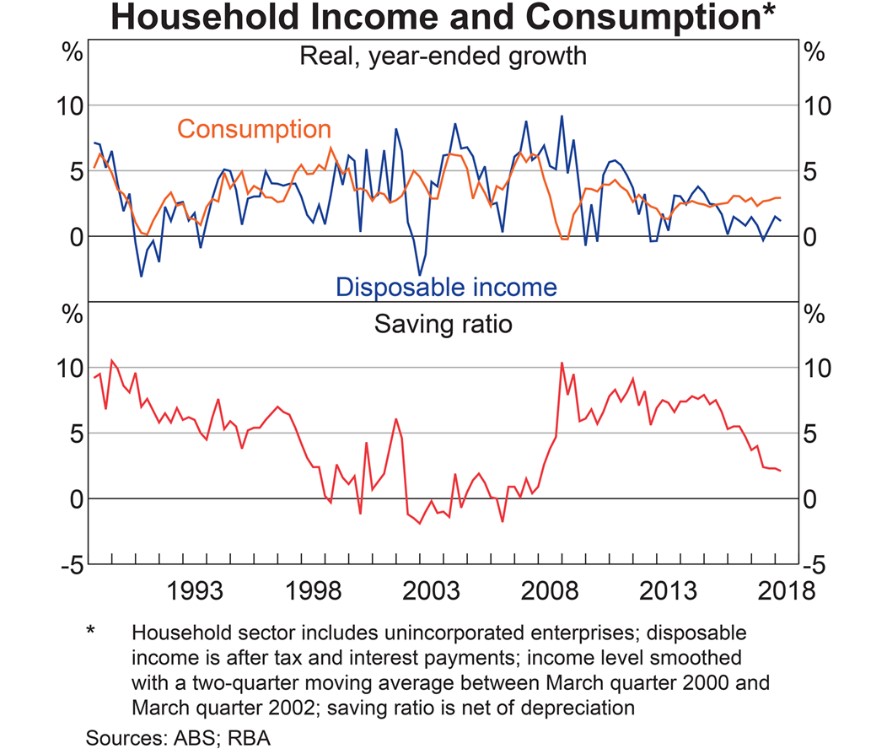

The failure to heed such policy advice warnings has seen a significant exacerbation of structural imbalances throughout the Australian economy through a rapid escalation in recent years of Australian household debt, net foreign debt, asset prices such as housing, and a significant decline in both household and national savings.

Ironically, the case to raise interest rates as a strategic pre-emptive policy tool to control and stem the growth of financial bubbles was actually outlined by Dr Lowe and his RBA colleague Dr Christopher Kent (who now holds the role of Assistant Governor (Financial Markets)) in a December 1997 RBA research paper, titled Asset Price Bubbles and Monetary Policy. In this paper, Lowe and Kent argued:

“Now suppose that the central bank, can increase the likelihood of a bubble bursting by raising interest rates. In this case it may make sense for the central bank to do so early on in the life of the bubble, even though this will increase the likelihood of inflation being below target in the near term. This is desirable, however, because it also decreases the chance of the bubble continuing, and hence, of much more extreme outcomes for inflation and output in the longer term.”

Note that in this statement, Lowe and Kent only make reference to taking strategic pre-emptive monetary policy action only early in the life of the bubble, not when the bubble has formed and growing to danger levels.

For a fully developed financial bubble growing to record and ever dangerous levels, Lowe and Kent offer a different policy prescription of how monetary policy should be used. Kent and Lowe state:

“The intuition is that if it is likely that the bubble will collapse under its own weight, the case for monetary policy to be used in an attempt to burst the bubble is much weaker. If there is a high probability that the bubble will burst of its own accord, monetary policy needs to be more concerned with the contractionary effects of the expected collapse; in some circumstances this might require a reduction in interest rates before the collapse actually occurs!”

The significance of this paragraph, if indeed the authors still hold this view, cannot be overstated, especially the implications that this paragraph holds for the economic welfare of ordinary Australian citizens, including:

One, the RBA’s inaction on raising official interest rates since Dr Lowe’s appointment as RBA Governor in September 2016 could well be a function of the RBA Governor waiting for the bubble to collapse as opposed to the Governor not recognising that a bubble actually exists!

Two, the RBA Governor by sitting on his hands over the past two years, potentially waiting for the bubble to burst, has actually allowed for the bubble to substantially grow during his tenure that has increased overall systemic Australian macroeconomic risk.

Three, unless the RBA Governor’s views have evolved, official interest rates may well be reduced even further (even perhaps to zero or negative interest rates) once the consequences of the bubble popping become more self-evident. Any such action would further exacerbate Australia’s economic structural problems and only delay our day of economic reckoning.

Having outlined these implications, it is important that Australians note, contrary to popular commentary, that the ‘bubble’ is not real estate prices which have been falling for several months in key markets such as in Sydney and Melbourne, but rather the bubble is the quantum of debt within the Australian economy which continues to grow, albeit at a slower rate as illustrated by the RBA’s own credit statistics (see table 1).

Table 1: Annualised Housing Credit Growth (RBA 2018 Data)

| March 2017 - March 2018 | June 2017 - June 2018 | |

| Credit Growth to Housing | 6.2% | 5.6% |

| Credit Growth to Owner Occupier Housing | 8.1% | 7.8% |

| Credit Growth to Investment Housing | 2.5% | 1.6% |

With ever growing debt, the Turnbull Government’s implementation of macroprudential controls via the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, at best, can only seek to reduce the level of risk associated with the Australia’s debt bubble.

These measures cannot, in and of themselves, shrink the debt bubble nor eliminate the inevitable catastrophic economic and social consequences that would result from an unanticipated bursting of Australia’s debt bubble emanating from an international economic shock.

This point was made by the current RBA Governor in his 1997 paper when he and Kent stated:

“While these [prudential regulation] measures do not rule out lending booms on the back of asset price rises, they help reduce the costs of asset price booms and busts.”

Moreover, this point was also made by former RBA Governor Glenn Stevens in an official 2012 speech [2] (while serving as RBA Governor):

“Macroprudential tools will have their place. But if the problem is fundamentally one of interest rates being too low for a protracted period, history suggests that the efforts of regulators to constrain balance sheet growth will ultimately not work. If the incentive to borrow is powerful and persistent enough, people will find a way to do it, even if that means the associated activity migrating beyond the regulatory perimeter.”

Hence, given these statements by current and former RBA officials, one can only conclude that the current economic strategy and monetary policy framework of the Turnbull Government (including the RBA) is to further pursue economic growth via ultralow interest rates and further exacerbation of Australia’s household and foreign debt bubbles until they ultimately break.

Not only is this economic strategy reckless and will result in economic devastation for hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Australians, it represents a crisis of national public policy and a chronic failure of the framework that underpins the conduct of Australia’s monetary policy.

[1] https://www.spectator.com.au/2017/08/trapped-by-cheap-credit/

AUD

AUD

Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...