Recent Posts

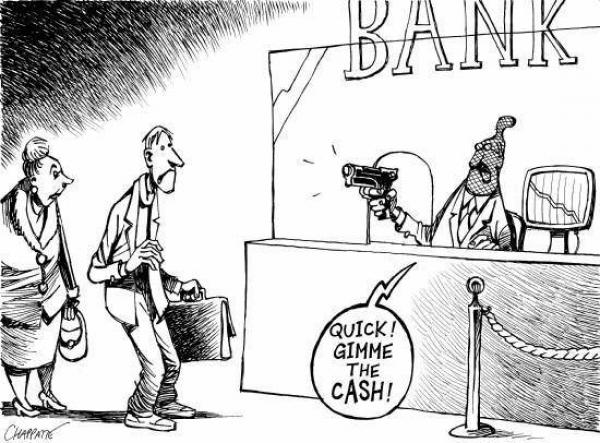

Will The Prime Minister Order A 'Smash And Grab' Of Bank Deposits?

Posted by on

Among the people, confidence in the Australian and international banking system is becoming precarious.

Ten years on from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and both Australia and the world are faced with:

- record levels of Australian domestic and global debt (including as a proportion of the size of the Australian and global economies respectively);

- a breakout of inflation across the developed and developing world;

- rising global interest rates; and

- lingering systemic challenges dating back to 2008 involving the banking sector and capital markets.

This combination of factors has heightened concerns that Australia and the world are not on a sustainable economic path and that a new economic and financial crisis is almost inevitable.

Of particular concern to economic and market observers is whether financial institutions operating in Australia have sound business models given the heavy exposure that these institutions have to mortgage debt and the Australian housing market.

Moreover, these observers ponder whether these institutions have sufficient capital reserves capable of absorbing losses that may result in the event of a global economic shock which would:

- place significant strain on the international wholesale credit market both in terms of the availability and price of international credit (i.e. higher international interest rates); and

- cause a detrimental impact on the Australian economy via lower (or negative) economic growth, higher unemployment and higher rates of defaults among Australian households who currently carry record levels of outstanding debt.

These concerns have been exacerbated given recent revelations detailed at Royal Commission into Banking relating to the issuing of loans against poor underwriting standards to customers who lack the capacity to meet their debt obligations.

Against this backdrop and given the recent experience of banks such as Lehmann Brothers (US), Northern Rock (UK) and Laiki (Cyprus) as well as controversial monetary policies such as quantitative easing and negative interest rates, citizens across the world (including Australians) remain anxious as to how they can weather the coming financial storm and preserve their wealth.

Fuelling such anxiousness is also the experience of ordinary Greeks and Cyprians who, in the wake of the 2012 Greek Sovereign Debt Crisis:

- were unable to have readily access to their money due to imposed capital controls; and

- lost a significant amount of their cash holdings, in the specific case of the Bank of Cyprus, due to a forced confiscation (or ‘bail-in’) of retail bank deposits in order to save the bank of imminent bankruptcy.

The Bank of Cyprus bail-in (the world’s first) involved the mandatory confiscation of 47.5 per cent of uninsured retail deposits above 100,000 euros in exchange for share equity in the bank.

This episode has had a significant chilling impact on confidence that citizens across the world have with the banking sector.

In light of recent actions undertaken by the G20 and the Australian Government, Australians rightly have asked themselves whether a bail-in of Australian retail bank deposits is possible if conditions similar to 2008 present themselves again.

To answer this question, Australians need to first recognise that a global effort has been underway in the post-GFC era to develop an international bail-in framework, to which the Australia Government has been a participant.

As early as the 2010 G20 meeting in South Korea, global policy makers have sought to develop new financial and regulatory tools that would ensure that Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs) do not pose a future systemic risk to the global economy and therefore do not pose future burdens on governments and taxpayers via a future bail‑out of the banks.

Indeed, the G20 (which includes Australia) in 2010 resolved:

“We reaffirmed our view that no firm should be too big or too complicated to fail and that taxpayers should not bear the costs of resolution. We endorsed the policy framework, work processes, and timelines proposed by the FSB [Financial Stability Board] to reduce the moral hazard risks posed by systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) and address the too‑big-to-fail problem.”

Subsequent to this resolution, governments around the world developed proposals in collaboration with international bodies such as the Financial Stability Board that would meet the aspirations of the G20.

These proposals culminated in the agreement of G20 members (including Australia) at the 2014 Brisbane summit meeting to the resolution that:

“We welcome the Financial Stability Board (FSB) proposal as set out in the Annex requiring global systemically important banks to hold additional loss absorbing capacity that would further protect taxpayers if these banks fail.”

Publicly, this ‘loss absorbing capacity’ encompassed capital instruments such as ‘hybrid securities’, that is bonds and convertible notes that have the ability to be converted into share equity if required to save the bank, although uninsured retail bank deposits were never excluded from this definition.

Subsequent to the 2014 G20 resolution, Australia via the Abbott and Turnbull Governments sought to implement the FSB proposal through domestic legislation.

This was achieved in February 2018 through the enactment of the Financial Sector Legislation Amendment (Crisis Resolution Powers and Other Measures) Act 2018 , which, in effect, amended the Banking Act 1959 to provide the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) with new regulatory tools to deal with a new financial crisis including bail-in powers, otherwise known as ‘conversion and write-off provisions’.

These powers, according to the Government, provide APRA with the legal power to bail-in Australian issued hybrid securities which currently stand at approximately $AUD 100 billion in market value.

However, despite this explanation, the legislation has been subject to significant public controversy and debate, specifically relating to the question of what can APRA precisely order a ‘bail-in’ of and whether retail bank deposits are included?

The debate hinges specifically on Section 31 of the Financial Sector Legislation Amendment (Crisis Resolution Powers and Other Measures) Act 2018 which defines conversion and write-off provisions as:

“the provisions of the prudential standards that relate to the conversion or writing off of:

(a) Additional Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital; or

(b) any other instrument.”

To some commentators such as Martin North from Digital Finance Analytics, this section is ambiguous and causes confusion given that neither the Financial Sector Legislation Amendment (Crisis Resolution Powers and Other Measures) Act 2018 (or the legislation’s Explanatory Memorandum ) or the Banking Act 1959 provide any specific definition or guidance as to the meaning or ‘any other instrument’ or the word ‘instrument’.

In the Australian economic, accounting and banking context, the word ‘instrument’ has been used in different contexts to mean either a ‘financial instrument’ or ‘capital instrument’.

For example, with regards to the former, both the Reserve Bank of Australia as well as International Financial Accounting Standards have defined ‘financial instruments’ to include retail bank deposits.

Alternatively, APRA has referred to the word ‘instrument’, for example, through Prudential Standard APS 111 Capital Adequacy: Measurement of Capital to not include retail bank deposits being considered as part of the banks’ ‘capital structure’[1].

While the Morrison Government including the Commonwealth Department of the Treasury, the RBA and APRA have all denied that either insured or uninsured retail bank deposits could be included under the definition of ‘any other instrument’, neither the Turnbull or Morrison Governments have taken any additional steps to clarify the legislation and provide legal assurance by explicitly excluding retail bank deposits.

In addition, public nervousness among Australians as to the safety of their bank deposits has been amplified given the implementation of the ‘Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive’ by the European

Union and the ‘Open Bank Resolution Policy’ by the New Zealand Central Bank, which, in both cases are an official bail-in policy that allows what occurred in Cyprus to occur either within Europe Union member countries or in New Zealand respectively.

In the case of New Zealand, their regulatory prudential system possesses inherently different values to that of Australia given that the New Zealand Central Bank has no legal requirement to protect depositors, whereas APRA, in the Australian context, does by virtue of Section 12 of the Banking Act 1959.

As Australia heads into the coming crisis, Australians need to individually consider whether retaining their wealth within the banking system is a prudent activity given the ambiguity over APRA’s legal power, especially given:

- recent statements by APRA’s Chairman that ‘caveat emptor’ (i.e. let the buyer beware) applies within the Australian context; and

- that APRA is not legally obliged to protect ‘deposits’, which in particular circumstances could be understood to be different to ‘depositors’.

As the law stands today, there is a real material risk that APRA (with the implicit blessing of the Prime Minister and his Cabinet) could well order a ‘smash and grab’ bail-in of retail bank deposits if a domestic authorised deposit-taking institution (i.e. bank) does indeed experience liquidity or solvency issues.

For those Australians who wish to retain ultimate control over their wealth, asset classes other than those that are in digital or paper form which are outside of the banking system should be considered.

For over 5000 years, these asset classes have typically included physical assets such as land, gold and silver, collectables and fine art among others.

[1] The capital structure includes Common Tier Equity, Additional Tier 1 Capital and Additional Tier 2 Capital.

AUD

AUD

Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...