Recent Posts

The Federal Budget which Destroyed Australia0

Posted by on

In years to come, the 2020-21 financial year (FY20-21) Federal Government budget will be judged in Australian history as the largest financial catastrophe in the history of Australia.

The budget, which was handed down by Treasurer Josh Frydenberg MP on 6 October 2020 as part of the Morrison Government’s ongoing economic response to the COVID-19 pandemic, delivered the largest annual nominal budget deficit in Australian history and the largest annual budget deficit as a proportion of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) since the end of World War 2 (WWII).

The budget is a financial calamity for Australia because it blows a gaping black hole in the finances of the Australian Government as far as the eye can see with no prospect of a budget surplus being delivered and, by consequence, the repayment of either the government’s existing debt or the debt accumulated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To add insult to injury, a cadre of professional economists and vested interested stakeholders (as outlined in the article ‘Democracy will destroy the Australian Dollar via runaway inflation’[1]) formed a pro-stimulus consensus during the COVID-19 pandemic to not only encourage the scale of the budget deficit announced by the Morrison Government, but also in some cases to argue additional economic stimulus which would further enlarge the budget deficit.

While attempting to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 and the resulting economic lockdown as well as save Australia’s household debt bubble from collapse, the pro-stimulus cadre have attempted to argue that continuous budget deficits and accumulating government debt is not an insurmountable challenge to Australia because of our collective heroic economic efforts in the aftermath of WWII.

In the 2.5 decades after WWII (i.e. 1945 to 1970), Australia’s federal gross government debt as a proportion of nominal GDP dramatically shrank despite persistently small budget deficits, through significantly growing:

- Australia’s population;

- the Australian economy; and

- Australia’s money supply (i.e. inflation).

On closer examination of this period, statistical evidence emerges which demonstrates that Australia in the coming one to two decades from FY19-20 onwards will not be able to replicate what Australia previously achieved in the post-WWII period.

When examining the federal budget closely, it quickly dawns on any observer that the scale of the fiscal challenge to not only stabilise government debt but to reduce it requires drastic austerity including significant cuts to federal government expenditure, especially in social welfare, health and education, if runaway inflation or even hyperinflation is to be avoided.

International empirical evidence has emerged that such austerity will result in a catastrophic quantum of premature deaths potentially amounting to hundreds of thousands of Australians.

The $AUD 1.1 Trillion COVID-19 Mistake

As noted in previous columns[2], the actual public health risk posed by COVID-19 was not commensurate with initial forecasts of the number of people globally who may have potentially died from COVID-19[3].

Only in the past week has the World Health Organisation (WHO) suggested that up to 10% of the world’s population or approximately 780 million people may have already been infected with COVID‑19 meaning that the Infection Fatality Rate is 24 times lower than suggested in March 2020, making COVID-19 statistically insignificant from influenza[4].

Moreover, the WHO has warned against government imposing national or regional lockdown restrictions in a primary control response to COVID-19 given that the economic, social and health costs associated with lockdowns outweigh any benefits achieved in containing the spread of COVID‑19[5].

On both of these counts, there appears to be no legitimate public policy justification for the COVID‑19 lockdown restrictions or the subsequent fiscal and monetary economic stimulus.

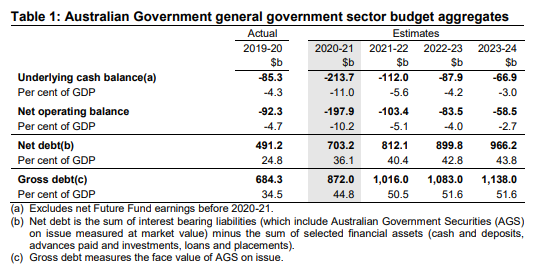

According to Table 1[6], an underlying cash balance deficit of $85.3 billion was achieved in FY19-20 in response to the closing of Australia’s international border and the initial internal lockdown policies which commenced in February 2020.

Moving forward, deficits of $AUD 480.5 billion are expected to be incurred from FY20-21 through to FY23-24 (i.e. the forward estimates). In total, the deficits over five financial years which are expected to be incurred as a result of Australia’s reaction to COVID-19 is expected to reach $AUD 565 billion.

However, as can be seen by Table 1, a sizeable deficit of $AUD 66.9 billion (or 3% of GDP) is expected to be incurred in FY23-24, with no hope the budget returning to a balanced budget meaning that further deficits are expected to be incurred throughout the decade. Indeed, by FY 2030-31, the federal budget assumes that the deficit would reduce in size to 1.6% of GDP or $AUD 52.8 billion.

Moreover, with these persistent budget deficits, the budget assumes that by June 2031 gross government debt is expected to reach approximately 55.1% of nominal GDP or approximately $AUD 1.8 trillion whereas net government debt is expected to reach 39.6% of nominal GDP or $AUD 1.3 trillion, assuming that nominal GDP reaches $AUD 3.3 trillion in FY2030-31.

Compared to the actual gross government debt position recorded as of 30 June 2020 (i.e. the end of FY19-20), the response to COVID-19 is expected to cost the government more than $AUD 1.1 trillion noting that it is unclear as to which financial year will the first federal government budget surplus be delivered meaning that the gross government debt to nominal GDP ratio will rise beyond the 55.1% figure estimated for FY30-31.

Optimistic Economic Assumptions

While the long‑term cost of COVID-19 to the Australian Government is expected to be in excess of $AUD 1.1 trillion over the coming decade and beyond, it is important to note that the costs indeed may be in fact more.

Embedded in the Federal Budget are a range of economic assumptions which on the surface appear to be optimistic which if they don’t materialise will result in:

- lower rates of economic growth;

- smaller collections of tax revenue;

- larger budget deficits; and

- greater government debt.

In particular, the budget’s more optimistic projections assume that:

- a COVID-19 vaccine is readily available to be rolled out en masse by 1 July 2021;

- private final demand will turnaround by 10% from a contraction of -3.5% in FY20-21 to growth of 6.5% in FY21-22;

- Australian real GDP will turnaround by 6.25% from a contraction of -1.5% in FY20-21 to growth of 4.5% in FY21-22;

- the global economy will experience a sharp recovery in calendar year 2021; and

- there will be no other economic recession (i.e. periods of negative economic growth) during the coming decade.

Given the highly uncertain environment caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the pre-existing structural problems in both the Australian and global economies, it is perhaps safer to assume that the scale of the damage to the finances to the Australian Government is worse than as presented in the FY 20-21 budget.

Australian History Will Not Repeat Itself

In both the run-up to the federal budget as well as after its release, multiple Australian economist and journalists[7] have suggested that the projected deficits and government debt do not pose an existential threat to the Australian Government given that larger deficits and debts relative to GDP have been overcome in the past[8].

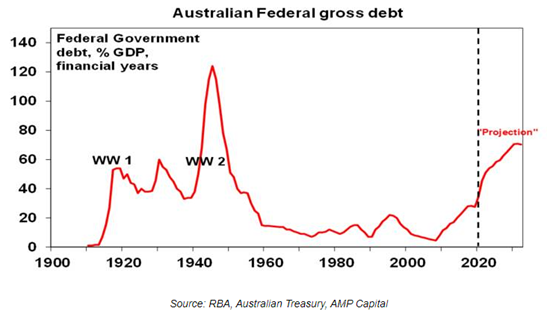

As can be shown in Diagrams 1 and 2, the period during WWII saw war-related expenditure skyrocket resulting in the Australian Government’s annual deficit ballooning out in excess of 25% of nominal GDP and gross government debt ballooning out to approximately 120% of nominal GDP.

In the 25 years after WWII (i.e. 1945 to 1970), both the annual deficit and gross government debt as a proportion of nominal GDP shrank dramatically. Gross federal government debt shrank to approximately 8% of nominal GDP by FY1973-74[9] and net federal government shrank to 0.9% in FY1970-71[10].

The shrinkage in the Australian Federal gross government debt to nominal GDP ratio was despite a series of budget deficits being delivered during in the 1950s and 1960s by both the Chifley and Menzies’ Governments.

Diagram 1: Australian Federal Budget Deficit as a proportion of Nominal GDP

Diagram 2: Australian Federal Gross Government Debt as a proportion of Nominal GDP

To understand how this significant economic feat was achieved, a closer examination of the:

- size and demographic profile of Australia’s population;

- Australian economy; and

- structural and discretionary dynamics of the Federal Budget

is required.

Once these factors are closely considered, it becomes evident that:

- the post-WWII period and the coming one to two decades differ by a significant degree given a range of structural differences; and

- the scale of the changes that Australia must undertake in the coming one to two decades in order to reflect what occurred post-WWII are drastic and unlikely.

Table 2 highlights nine core factors which reflects:

- how gross government debt relative to nominal GDP was able to shrink post-WWII from 120% in FY45-46 to 8% in FY73-74; and

- why these factors either are unlikely to apply in the coming 1 to 2 decades following the FY19-20.

Table 2: Core Factors for Post-WWII Shrinkage of Gross Government Debt to Nominal GDP and Implications For Australia in 2020 and Beyond

| No | Category | Post WWII Period | FY19 -20 & Beyond |

| 1 | War/Defence Spending | Significant war related spending during

WWII was discretionary in nature and was severely wound back at the

conclusion of WWII.

In the FY1945-46 Federal Budget, 55.6% of total expenditure was related to the effort to win WWII. |

The defence budget is structural nature and

has a cost base of $AUD 35 billion per annum or 6% of total federal

government expenditure.

The current defence budget supports the annual costs in operating Australia’s defence forces and supports the acquisition of advanced military equipment which goes beyond the current budget. While savings within the defence budget are achievable, any possible efficiency gains would be very small relative to overall government expenditure. Any cuts to defence beyond efficiency gains would result in reduction in Australia’s military capability. |

| 2 | Population | From 1945 to 1970, Australia’s population increased

by 70% from 7.4 million to 12.6 million[11].

This growth was a combination of an increase in domestic marriages, a domestic baby boom and significant European immigration. |

In March 2020, Australia’s population was estimated

to be 25.6 million people[12].

For Australia to replicate a similar population growth trajectory as in the post-WW2 period, Australia’s population would have to increase to 43.6 million people. Note that in the 2015 Intergenerational report[13], Australia’s population was forecasted to reach 39.7 million people by 2054-55[14]. |

| No | Category | Post WWII Period | FY2019 - 20 & Beyond |

| 3 | Age Demographics | In 1945 the proportion of the Australian population that was 65 years old or above was 7.8%[15]. | In 2019, the proportion of the Australian

population that was 65 years old or above was 15.9%[16].

Australia’s demographic profile is expected to worsen in the coming years meaning that the Federal Government’s two largest expenditure portfolios, i.e. social security and welfare and health will likely experience significant growth given Australia’s demographic profile. |

| 4 | Nominal GDP Growth | From FY 1949/50 through to FY 1970/71 period, Australia’s nominal GDP increased 574.78% from $AUD 5.23 billion through to $AUD 35.29 billion[17]. | Australia’s nominal GDP at the end of FY2019-20 was

$AUD 1.98 trillion[18].

According to the FY2020-21 Federal Budget, nominal GDP is expected to grow to a maximum of $3.3 trillion by FY30-31 which represents growth of nominal GDP by 66%. |

| 5 | Household Debt | As of 1945, Australian Household Debt as a

proportion of nominal GDP was 4.3% and grew to 20% by 1970s[19].

Despite this growth in household debt during this period, Australia’s financial system was heavily regulated and access to credit for Australian households was curtailed. |

Australian Household Debt as a proportion

of GDP is 126.9% as of June 2020[20].

This is almost a record high in Australian history and one of the highest

ratios in the world.

With household balance sheets already severely stretched, Australian households have limited capacity to contributing to growing nominal GDP over the coming 1 to 2 decades. This is especially so given that official interest rates are currently at a historical record low of 0.25% meaning that the capacity of monetary policy has largely been exhausted. |

| No | Category | Post WWII Period | FY2019 - 20 & Beyond |

| 6 | Unemployment | In the post WWII period under the Bretton Woods International Monetary System, the Australian economy experienced full employment which from 1946 to 1974, official unemployment averaged below 2%.[21] | According to the FY 20-21 Federal Budget, unemployment is expected to peak at 8% by the end of calendar year 2020 and is expected to reduce to 6.5% by the June quarter 2022[22]. |

| 7 | Yields on Commonwealth Government Bonds | From FY49-50 through to FY70-71, the yields on

Federal Government:

|

As of 14 October 2020, the yields on Federal

Government bonds are at record lows given the monetary policy intervention of

the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) with:

meaning that bond yields can easily increase by a factor larger than the increase of FY49-50 and FY70-71 which in turn could lead to a blow out in the Federal Government’s interest expense cost on both: - newly issued bonds; and - existing bonds which are required to be rolled over. |

| 8 | Structural

Budget Dynamics |

In the FY45-46 Federal Budget, only 12.3%

of total expenditure was dedicated to social welfare and health spending via

the ‘National Welfare Fund’.

(Education spending was still the main purview of State and Territory Governments at this point). Contributions to the ‘National Welfare Fund’ and direct payments to the states relating to social welfare, health and education reached to 20.0% of total expenditure in the FY70-71 Federal Budget. |

According to the FY20-21 Federal Budget,

starting in July 2021, 58.8% of the total Commonwealth expenditure will go

towards:

Given the demographic profile of Australia’s population (i.e. the ageing of the population), there are strong in-built cost drivers which will drive up the federal spending in social welfare and health portfolios in the coming one to two decades. |

| No | Category | Post WWII Period | FY2019 - 20 & Beyond |

| 9 | Gross and Net Foreign Debt | During the post-WWII period, Australia’s

gross foreign debt levels were relatively low compared to pre-WWII levels.

By 1970, Australia’s gross foreign debt to nominal GDP was 11.5%, whereas net foreign debt to nominal GDP was 6.5%.[23] Moreover, the average annual interest cost from 1959 to 1970 for:

|

As of June 2020, Australia’s:

While Australia’s annual interest cost during FY19-20 for:

and given how low global interest rates are, only a small upward adjustment in interest rates will blow out the foreign debt interest costs leading to a balance of payments crisis given the size of Australia’s foreign debt. |

What can be seen by Table 2 is that the post-WWII period was a remarkable period in Australian history and Australia’s ability to reduce gross government debt as a proportion of GDP was driven by a range of unique factors which are unlikely to be replicated in the coming one to two decades from FY19-20 and beyond.

The implications of this critical finding are that:

- The structural financial hole which the Australian Government finds itself in is larger than what economists and commentators have suggested in the past 4 weeks;

- the scale of the fiscal challenge to balance the budget and to reduce the quantum of Commonwealth debt is immense and cannot be overcome via economic measures or population growth; and

- structural budget austerity will be required to achieve a sizeable budget surplus sufficient to reduce the gross government debt to nominal GDP burden; and

- if sufficient structural budget austerity is not achieved then Australia is likely to experience a currency and balance of payments crisis on a more extreme scale than what former Federal Treasurer Paul Keating experienced during the 1985-86 ‘banana republic’ balance of payment crisis.

- This is because of the scale of Australia’s foreign debt (to which public sector debt is and will be into the future a major component) can lead to a blow out in the current account deficit either through a sharp depreciation in the Australian dollar or though rising global interest rates.

These implications carry significant economic and financial consequences into the future for both Australia as a nation and for individual Australian citizens. As these implications are poorly understood, individual Australians, if left unprepared, may experience adverse economic and social outcomes when the moment of crisis arrives.

The Scale of Australia’s Federal Fiscal Challenge

Any attempt to balance Australia’s Federal Budget and to repay the scale of ever accumulating federal debt will require a significant multi-year fiscal austerity package that delivers consecutive sizeable budget surpluses.

As noted in the article, Democracy will destroy the Australian Dollar via runaway inflation’, given Australia’s pro-economic stimulus political consensus and the nature of Australia’s democratic political system, the need for such fiscal austerity is likely to be borne from an economic crisis driven by concerns of Australia’s international creditors rather than by an organic internal political movement and corresponding agenda.

As outlined by Alesina, Favero and Giavazzi (2019)[24], other developed countries across Europe and North America have been forced to implement fiscal austerity packages due to concerns from bond holders as to the solvency and creditworthiness of their governments.

These austerity packages have either included:

- rising taxes or other government charges;

- reducing expenditure;

- privatising government assets; or

- a combination of all three.

Interestingly, the analysis by Alesina, Favero and Giavazzi demonstrates that fiscal austerity attempted through raising taxes does little to reduce budget deficits, given that raising taxes results in:

- greater economic uncertainty and lower business confidence;

- lower levels of investment;

- larger losses of economic output; and

- lower tax revenue growth over the medium term.

Alternatively, fiscal austerity implemented by cutting government spending does not adversely impact business confidence or investment and thus leads to a minimal loss of economic output over the medium term. As a result, fiscal austerity via a sustained multi-year program of cutting government spending leads to a sustained reduction in the size of the budget deficit.

The only downside of a fiscal austerity package driven by reducing government expenditure is that the financial, and as a result the political, impact is felt immediately whereas the economic impact of tax increases are felt with greater effect in later years.

Thus, any attempt to deliver a federal budget surplus and repay Commonwealth debt will require a disproportionate quantum of cuts to federal government spending as opposed to raising federal taxes.

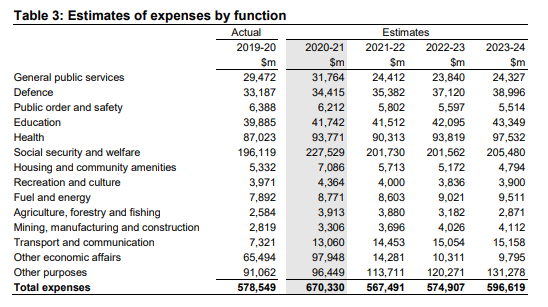

When examining the future estimates of federal government spending through to FY2023-24 (see Table 3 below), we can see that a substantial amount of additional economic stimulus spending dominates the current financial year (i.e. FY2020-21) which is shown in:

- “other economic affairs” (this line item is expenditure dominated by the JobKeeper program); and

- “social security and welfare” (which includes the JobSeeker payment).

However, beyond this financial year, federal government expenditure is dominated by pre-COVID-19 recurring government spending. As noted in Table 2 above, this spending is dominated by social security welfare, health and education which comprises more than 58% of budget expenditure over financial years F21-22, FY22-23 and FY23-24 whereas defence spending only makes up approximately 6.3% over the same period.

As noted in Table 1 above, the federal deficit is assumed to remain large over the coming three financial years and will remain persistently above at least $AUD 50 billion per annum through to FY 30-31. As noted above, circumstances can easily arise (e.g. a prolonged COVID-19 pandemic, weak economic growth or rising interest rates) which result in a larger budget deficit well above what has been estimated.

Thus, the scale of the austerity spending cuts required to produce a budget surplus remains well in excess of $AUD 50 billion per annum which are not easily achievable without significant spending cuts to social security, health and education.

During an economic crisis where the budget deficit has blown out above estimate, the scale of austerity spending cuts could be well above $AUD 100 billion per annum.

Given that particular State and Territory Governments are also carrying a significant debt burden, in particular Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia and the Australian Capital Territory, it is likely austerity at this level of government may also be required during an economic crisis which would:

- detract from economic growth as measured by GDP;

- exacerbate the federal deficit; and

- require even larger cuts to federal government expenditure.

The Social Cost of Austerity

Such significant cuts to sensitive portfolios will carry significant and long-run implications.

Indeed, in the post 2008 Global Financial Crisis era an increasing amount of academic research has been conducted on the effects of the fiscal austerity which has been implemented by various governments including the United Kingdom (UK) and in the European Union.

According to one European academic paper (Stuckler and co)[25], any major cuts to government spending, especially in the areas of social security welfare and health are likely to result in two main effects:

- the ‘social risk effect’ – which refers to the social consequences from austerity which includes greater unemployment, crime, poverty, suicide, homelessness, poor diets which can culminate into an increase in infectious diseases, physical harm, multiple morbidities, premature mortality;

- the ‘health care effect’ - which refers to citizens being restricted access to health care either through cuts to health care services or reductions in health services.

These effects combined translate to a significant number of premature deaths as measured by the mortality rate, especially in countries with an older demographic profile. As noted by Stuckler and Co (see footnote 23), Italy recorded its highest mortality rate since WWII in 2015 and the UK saw its highest mortality rate in 50 years also in 2015.

One 2017 UK study suggested that the austerity implemented by the Tory Government of David Cameron led to approximately 45,000 premature deaths per year or up to 130,000 people[26]. The authors of the paper described the impact of austerity as ‘economic murder’[27].

When fiscal austerity is required to be imposed in Australia, similar effects can be expected which, given:

- Australia’s demographic profile; and

- the concentration of federal government spending in social security and welfare and health

are likely to result in the premature deaths of tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of Australians. The death of these individuals will be the real tragedy of the Morrison Government’s FY20-21 Federal Budget – a death toll far greater than the risk posed by COVID‑19.

Conclusion

Australia’s existing national economic problems have been compounded by the worst federal budget in Australian history.

The budget delivered the largest annual fiscal deficit in Australian history in nominal terms and the largest budget deficit in real terms since World War 2. In its totality, the reaction of the Federal and State/Territory Governments are projected to rack up over $AUD 1.1 trillion from FY19-20 through to FY2030-31 in response to COVID-19.

As a result, gross and net Federal Government debt is expected to balloon out by 2030 to $AUD 1.8 trillion (or 55.1%) or $AUD 1.3 trillion (39.6%) respectively.

As noted in other articles, the public health risk posed by COVID-19 did not justify this level of expenditure and the quantum of fiscal and monetary stimulus was in reality designed to rescue Australia’s largest household debt bubble and Australia’s commercial banks by minimising unemployment and the scale of household and business defaults.

While the economic stimulus package delayed a day of reckoning among a large number of Australian households who possess:

- over inflated assets;

- significant debts; and

- little savings

the underlying structural problems facing Australian households and the broader economy have not been solved and in fact have only been exacerbated.

Unlike in the post-WWII period where Australia was able to dramatically grow its population and economy which resulted in gross government debt to GDP to dramatically shrink over 25 years through to 1970, a range of factors demonstrate that such a repeat performance in the coming 25 years is not possible.

In order to prevent a balance of payments and currency crisis which will ultimately result in runaway inflation, fiscal austerity is required at both the federal government as well as the state and territory government levels.

As demonstrated by academic research from the UK and Europe, fiscal austerity will result in significant adverse social and health outcomes, in particular an increase in the mortality rate and premature death.

Given that Australia has an ageing population and that federal government spending is concentrated in social security and welfare, health and education, fiscal austerity in Australia, especially if conducted during an economic crisis, will require significant cuts that will result in a reduction of disposable income to Australia’s poor, disabled and elderly as well as a restriction of access to health services.

Based on international experience, this should result in a sharp increase in Australia’s mortality rate resulting in the premature deaths of tens of thousands if not hundreds of thousands of Australians.

The tragedy of 2020 is that while Australia’s political class moved heaven and earth to prevent the death of older Australians who were at risk from COVID-19, its irresponsible and disproportionate actions will result in a far higher death toll, especially of older Australians, in the years to come.

John Adams is the Chief Economist for As Good As Gold Australia

[1]https://www.adamseconomics.com/post/democracy-will-destroy-the-australian-dollar-via-runaway-inflation

[2] See the following article from April 2020: https://www.adamseconomics.com/post/australia-has-been-economically-destroyed-within-4-weeks

[3] For example, Imperial College suggested that up to 40 million people globally were at risk of death and

the Doherty Institute estimates that up to 150,000 Australians were at risk of death if no mitigation strategies were implemented.

[4]https://www.en24news.com/2020/10/covid-19-780-million-people-infected-against-35-million-officially-the-who-is-self-critical.html

[5] See https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/science-and-disease/exclusive-top-disease-detective-warns-against-return-national/ and https://nypost.com/2020/10/11/who-warns-against-covid-19-lockdowns-due-to-economic-damage/

[6] Table 1 is sourced from the FY20-21 Federal Budget, Budget Paper 1, Statement 3, page 3-6

[7] Examples include ABC economics writer Gareth Hutchens, EY Chief Economist Jo Masters and Castlemaine Institute Warwick Smith.

[8] See the following: https://www.michaelwest.com.au/history-shows-future-generations-dont-need-to-suffer-from-government-debt/ or https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-10-09/federal-budget-2020-debt-deficit-blowout-explained/12741472

[9]https://www.ey.com/en_au/covid-19/oceania-covid-19-response/is-australias-debt-level-unprecedented

[10] See FY2020-21 Federal Budget Paper - Statement 10, page 11-12.

[11]See the following ABS publication: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/2f762f95845417aeca25706c00834efa/e2f62e625b7855bfca2570ec0073cdf6!OpenDocument

[12] https://archive.budget.gov.au/1945-46/Budget_1945-46.pdf

[13] https://treasury.gov.au/publication/2015-igr

[14] Another important point to note is that the 2015 Intergenerational Report forecasted that Australia’s population was expected to reach 28 million people by 2025, which now is unlikely.

[15] See ABS publication: “Australian Historical Population Statistics – 3105.0.65.001, 2016” - https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/second+level+view?ReadForm&prodno=3105.0.65.001&viewtitle=Australian%20Historical%20Population%20Statistics~2016~Latest~18/04/2019&&tabname=Past%20Future%20Issues&prodno=3105.0.65.001&issue=2016&num=&view=&

[16] https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/1CD2B1952AFC5E7ACA257298000F2E76?OpenDocument

[17] See “Australian Economics Statistics 1949-50 to 1996-97, Occasional Paper No. 8, Table 5.1a: Expenditure on Gross Domestic Product at Current Prices” - https://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/frequency/occ-paper-8.html

[18] See the ABS’ “Australia’s National Accounts” publication - https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/national-accounts/australian-national-accounts-national-income-expenditure-and-product/latest-release

[19] See Graph 5 for the following speech by RBA Deputy Governor Ric Battelino - https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2007/sp-dg-250907.html

[20] This data was calculated using household debt data from the RBA and nominal GDP data from the ABS.

[21]https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-10-11/federal-budget-why-frydenberg-wont-be-pursuing-full-employment/12751566

[22] See Federal Budget Paper 1 – Statement 2: Economic Outlook – Page 2-5

[23] See Table 1 from the 1992 publication by the Department of the Parliamentary Library: https://www.aph.gov.au/binaries/library/pubs/bp/1992/92bp26.pdf

[24] Alesina, A., Favero, C., and Giavazzi, F., (2019), “Austerity – When It Works and When It Doesn’t”, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, USA

[25] Stuckler, D.; Reeves, A.; Loopstra, R.; Karanikolos, M.; Mckee, M., (2017), “Austerity & health: the impact in the UK and Europe”, European Journal of Public Health, Vol. 27, Supplement 4.

[26] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/jun/01/perfect-storm-austerity-behind-130000-deaths-uk-ippr-report

[27] https://politicsandinsights.org/2017/11/16/austerity-is-economic-murder-and-bad-economics-says-cambridge-researcher/

AUD

AUD

Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...